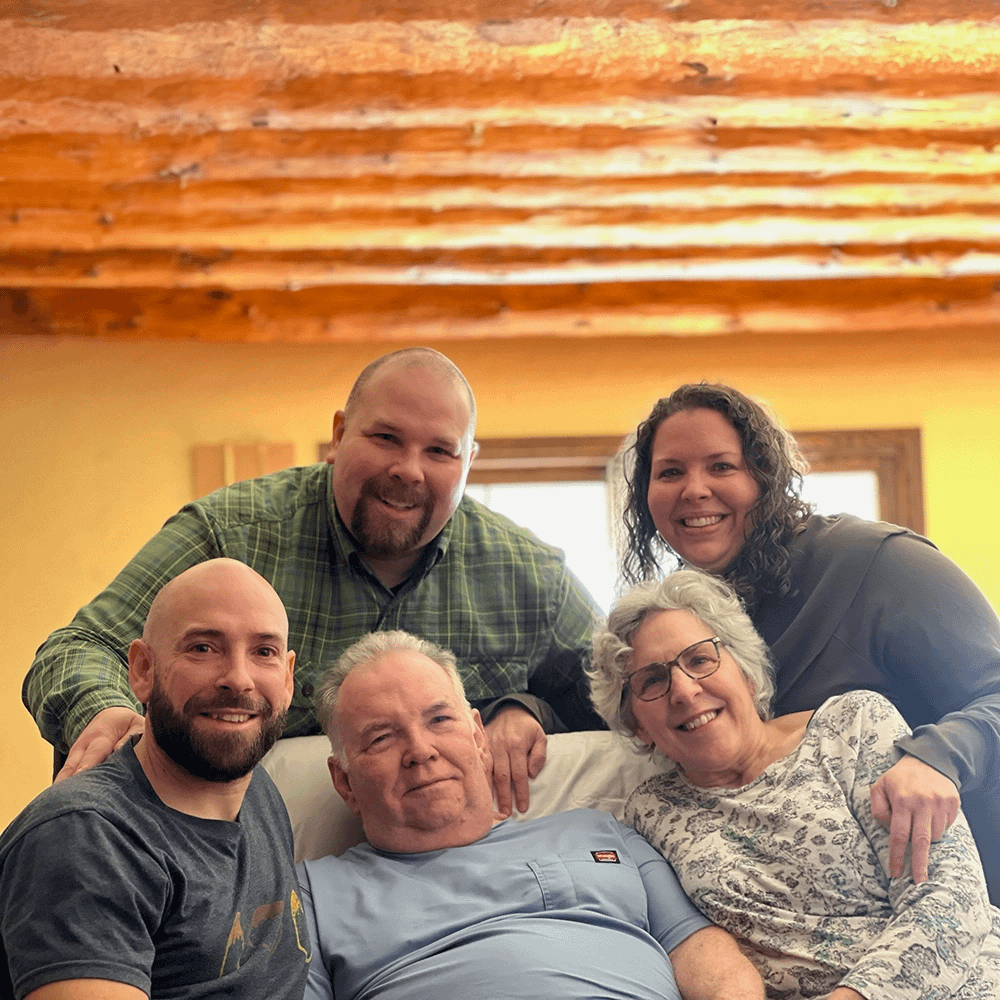

Ron Tanner was a singer, small business developer and community volunteer who moved from Illinois to Colorado in 2022 to access the state’s medical aid-in-dying law and end his suffering from corticobasal syndrome. His daughter, Ellen Tanner, his wife, Mary Tanner, and his daughter-in-law Ashley Baugh joined Compassion & Choices in March of 2024 to share about Ron’s end-of-life journey.

Mary Tanner, wife of Ron Tanner: Ron was always kind of a big presence in the room, even though he was short and stout. He had a lot of confidence. I think the fact that he was always singing in front of groups gave him an ease in front of people. He grew up singing in the church and had a gorgeous voice.

Ellen Tanner, daughter of Ron Tanner: Dad really valued serving his community and connecting with others through music. He devoted years and years of service to his church and his community — cantoring on Sundays, participating in the Knights of Columbus, rehearsing for community choir and special events. He was a very passionate, demonstrative, emotive person. That fire was always present whether it was watching the Cardinals or talking about a favorite song of his or …

Mary: Golf!

Ellen: Or golf. He always had a lot of passion and fire.

Mary: He and I met in high school. He sat behind me in Spanish class and absolutely drove me crazy drumming on his desk. We kept getting thrown together because our last names were close alphabetically. We became friends. Then, once I went away to college, he decided he wanted to date me. So we dated long-distance.

Ellen: In high school, each of them sat in the same desk for algebra but in different periods. They were writing back and forth to each other on the desk, not knowing who the other person was. They didn’t find out until years later, after they were married.

Mary and Ron were married in December 1975.

Mary: Ron and I loved mountains and rivers. We were not beach people. So we went camping a lot as a family.

Ellen: Some of the best life lessons I’ve ever learned were from Dad in a canoe on a river.

Mary: Imagine taking a family of five camping in a minivan with a canoe. Somehow he made it all fit perfectly.

Ellen: We’re all master packers, thanks to Dad.

Mary: Around 2014 or so, Ron had a personality change. He started getting really argumentative, more so than in the past. He became very difficult to live with. He became disorganized in his home office. And then his tremors started. His vocal quality changed. His regular doctor thought it might be Parkinson’s disease and referred him to a neurologist. In 2018 the doctors diagnosed him with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), but there were certain symptoms of his that didn’t fit the PSP pathology. Finally, in 2019 he saw a neurological ophthalmologist who diagnosed him with corticobasal syndrome. And it was pretty earth-shattering because there was no cure.

Corticobasal syndrome (CBS) is a rare neurological disorder that can affect both movement and cognition.

Ellen: Not only was there no cure, but there were no medications to address or slow the symptom progression.

Mary: There weren’t even any clinical trials to get into except to build data.

Over time, Ron’s ability to come up with words and phrases diminished. It would take 10 minutes for him to think of how to say what he wanted to. We found other ways, like using pictures, to help him communicate. The neurologist noted that Ron’s cognitive decline was pretty limited; his symptoms were primarily muscular and balance-related. He fell so many times.

Ellen: Within a month or two of his diagnosis, Dad made it very clear that he wished he could have medical aid in dying. He was a mover and a shaker his whole life and hated feeling out of control. The idea of being trapped in his body felt like hell on earth. He’d say, “I wish I could go somewhere I can die. You’ve got to get me out to Oregon or Colorado.” He had that conversation with my brother, Riley, many times, but he’d also talk to me about it. Ron Tanner was many things, but subtle was not one of them. He was very clear about how he felt.

Mary: We’d all gather together — the children, their spouses, Ron and me — in the living room and talk about Ron’s condition. What options do we have? Is there any way to help Ron get access to medical aid in dying?

Ellen: Unfortunately aid-in-dying medication is not authorized in Illinois, and Mom and Dad couldn’t afford to move or take up a second residence for an extended stay in another state. Moving for anyone is incredibly stressful, but especially a person with a degenerative neurological disease. And Dad was very explicit that although he wanted the option, he didn’t want to move. Because, he said, “I’ve lived in this town my whole life, this house for 35 years. My family is here, my community is here, and I want to spend my last days with them.” He really, really wanted that.

So we took the option off the table for the foreseeable future. Over the next three years, our family navigated the pandemic while spending as much quality time together as possible. Dad could no longer attend his daily therapy course, and his functional strength, balance and mobility declined significantly. He lost a great deal of his independence in activities of daily living.

Mary: Finally I couldn’t care for him at home anymore because he was so much bigger than me. In April 2022, he went on hospice and entered a skilled nursing facility. Around that same time, Riley and his wife, Ashley, moved home from Colorado.

Ellen: It was, for us, a godsend. Before the move, Ashley was talking to a doctor she knew who asked why she was moving back to Illinois. Ashley said, “My husband’s father is dying and we want to be there.” And the doctor asked her if she knew that she is open to prescribing medical aid in dying and has done so for previous patients. Ashley had no idea — and she’s a social worker.

It turns out that our assumptions about what was required to establish residency in Colorado were incorrect. All of a sudden it seemed like there might be a path forward if my dad was willing.

Ashley Baugh, daughter-in-law of Ron Tanner: We came back and informed everyone of what we had learned. Ron’s desperation by this point was so big that moving became more tempting once we realized that the time frame to establish residency was shorter than we thought.

Mary: We had multiple conversations with the doctor about what we would need to do. We talked as a family multiple times. There were a lot of logistics to figure out. Thankfully, as far as the cost went, my brother had made it known about six months earlier that if there was any way he could help Ron financially, he would.

Ellen: When we finally told Dad that we thought we could make Colorado happen, he relaxed. But we were terrified we weren’t going to be able to physically get him there.

Mary: Getting him on a flight, getting him off a flight, taking the hour-long ride to where we would stay. What kind of equipment would we need when we were there?

Ashley: Being in new environments was extremely stressful for him. That was compounded by the fact that he was prone to severe panic attacks and couldn’t move physically on his own.

Ellen: We had to figure out disability options with the airlines. We had to figure out how to get an accessible rental van.

Ashley: How to get Ron on hospice in Colorado, how to get him to the DMV to get an ID for residency’s sake.

Mary: Getting the hospice records transferred was itself a huge hassle. Then he was also a Medicaid patient, and the finances of everything became just one hoop after another.

Ellen: It was a nightmare.

Ashley: We were able to get things set up so that Ron could rent a space from a friend of ours to establish residency. But we didn’t want him to have to pass there. So it was important to find another space. We needed somewhere big enough for the whole family to gather around him and for a hospital bed, and also not to feel like we were putting anyone out. After lots of research and speaking to several death doulas in Colorado, we found a kind woman who agreed to host us at her retreat space.

After that, Mary and Ron had to have multiple telehealth appointments for Ron to establish care and discuss his wishes. He had to communicate that he wanted to use medical aid in dying, certify that he had a terminal illness and was on hospice, and then have an in-person appointment again to confirm everything.

Riley and I went to the pharmacy in person and had a sit-down meeting with the pharmacist. He explained everything, and we recorded what he said so that we could remember correctly and show it to the other family members as well. Then we put the medication in a safe place for 24 hours.

Ellen: The night before Dad was going to take the medication, there was a big, full moon, the last supermoon of the year. We all went out and looked at the full moon with Dad. That night we also started sending out word to close friends and extended family that Dad was planning to transition the next day. So he started hearing from people via FaceTime, video and audio messages, text messages, and pictures the things you don’t usually hear before you die, the things people say at your funeral or in a sympathy card after the fact. He got to hear all of it before he died. It meant so much to him and to us.

Ashley: The next morning, Ron was more alert than he had been in weeks. He had been so stressed from the travel and the ups and downs of getting to this point. But he said multiple times that he wasn’t afraid, that he was ready and even excited. He made the most of every moment of that entire day.

Mary: I know that Ron believed that this wasn’t the end. He saw it as a transition into another way of being.

Ashley: He envisioned canoeing down a river and meeting his dad and his grandpa.

Ellen: After breakfast that morning, we spent an hour just listening to music from a playlist of songs Dad loved and going around the room telling stories. We took turns lying on the bed with Dad and just having personal conversations with him. There was lots of laughter and tears, and listening or singing along to music, like “Leader of the Band” by Dan Fogelberg.

Mary: It’s a song Fogelberg wrote about his father who was a high school band director.

Ellen: Dad was always the leader of the band in our family. So we sang that song together to him before he took the medications. It was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever witnessed in my life. It was so healing.

Mary: It was 30 minutes between each dose. The last part, he had to suck up a very thick liquid through a straw, within 90 seconds.

Ashley: He had been practicing. Because he was a singer, his lungs were so strong. When the hospice nurse came in to check his pulse, he took one last gasp of air that startled us all. It felt like one last joke he was getting in under the wire.

Mary: After Ron died, our host brought a beautiful glass bowl of scented water. Ellen and I washed his body with it. It was very emotional and beautiful. Then, when the funeral home staff showed up, all the children helped lift his body onto the gurney, and we all walked out to the hearse with him. We waved goodbye as they drove off. Then we rang a gong to send his spirit. It was gorgeous.

Ron took his aid-in-dying medication and passed away on December 8, 2022.

Mary: The downside to all of this was that it was so weird coming home without him. If we had been able to do it here at home in Illinois, we wouldn’t have had that terrible long journey home.

Ellen: My dad’s mom is still living and wasn’t able to be there. I think it would have been very healing for her. This year has been hard on her, and I wonder if a lot of that is because she didn’t get to witness how joyful and beautiful and peaceful the end was for Dad. She saw the worst of it, and then he was just gone. And every single person in my family who was there has expressed just how powerful, beautiful and better than they could have ever imagined this was. My brother Alex and his wife were initially probably the most unsure and uncomfortable with Dad’s decision, and their whole perspective on it did a 180. It was healing for all of us.

Ashley: I work in mental health and had some reservations of my own about medical aid in dying in the past. But I hadn’t done much research on it and didn’t understand how it works. Once it becomes personal and you have a loved one facing that situation, and you’re watching them suffer every day and it’s not going to get better, well, that changes things. Once we understood the protocols and protections in place and just how intentional this has to be, and how much Ron desperately wanted this, it really changed how I thought of it. He wasn’t causing himself to die. He was just making the end of his life less agonizing.

Ellen: I’ve worked in long-term care for more than seven years. And I’ve watched many people at the end of their lives and worked closely with their family members. What is incredibly clear is that it doesn’t matter your religion or politics; when you’re seeing this firsthand, you know deep down what is humane and right and what isn’t. There aren’t many people who have watched death up close who don’t know that this isn’t right. It’s not OK to force dying people to suffer when they wouldn’t have to. Terminally ill Illinoisans shouldn’t have to leave their home to die peacefully.

Nothing advances our common cause of improving end-of-life care like real stories. Inspire others and drive change by sharing your story today.

Mail contributions directly to:

Compassion & Choices Gift Processing Center

PO Box 485

Etna, NH 03750