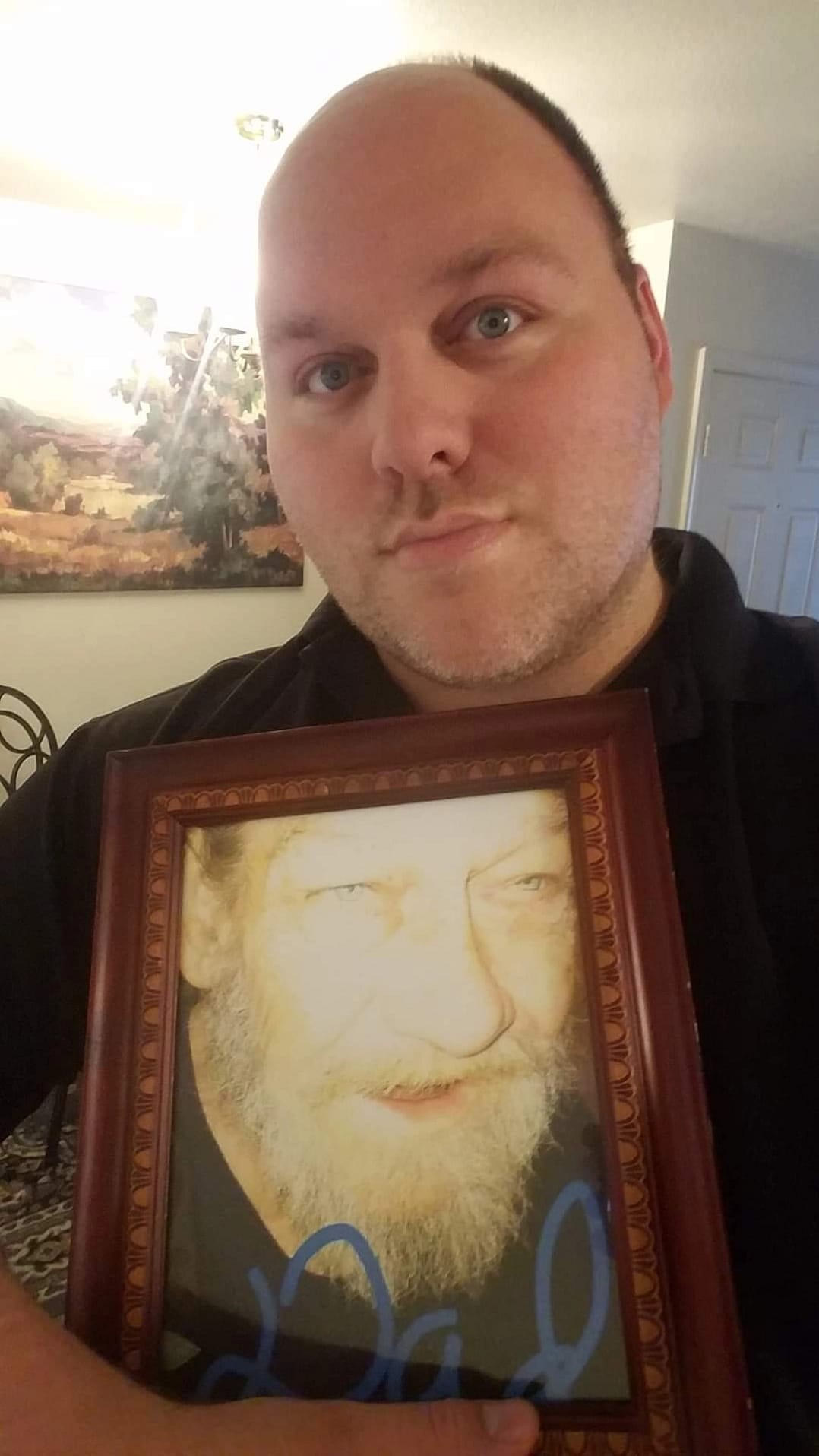

Robert shared his story in June of 2023.

In the spring of 2021, my dad started repeating himself a lot. Because he and I were sharing an apartment at the time, I noticed this and other strange symptoms — he’d get very bad headaches, was always thirsty and had very little appetite. He was losing weight, and some days his face was very pale.

Dad’s symptoms reminded me of my friend’s mother, who died of a very aggressive cancer. But I didn’t say anything to my dad about my suspicions. I didn’t want to scare him. It didn’t occur to me that he might also be keeping his own secret.

My father was very straightforward and outspoken. Either he liked a person or he did not; there was no in between. I fell into the former camp. Dad was my biggest fan, the person I could turn to for anything. As a gay man who struggled to make sense of my place in the world, I found a true friend in my father. When I came out to him at the age of 18, he said he had always known. He understood me in a way no one else could.

In late summer 2021, my dad learned that he had a mass in his left lung that appeared to be carcinoma, likely a result of decades of chain-smoking cigarettes. He didn’t tell me, I think because he didn’t know how. I wouldn’t discover Dad’s secret until November or December that same year, when we went together to our local urgent care center, and the doctor there pulled up Dad’s medical records to check the progression of the mass in his lung per the current scans. It was my nightmare brought to life.

For whatever reason, Dad was reluctant to see a pulmonologist. But shortly after the visit to urgent care, he did go see his primary care physician. She told me that she couldn’t prescribe him any stronger pain medication and that she recommended he go into hospice care — his cancer was that advanced.

Dad made it very clear that he did not want to go into a hospice facility. But it was also clear that he was in a lot of pain. He was crying a lot. I told him that the only thing I could think of that could ease his pain would be home hospice care. “Just remember, I’m here, and they won’t take you out of the apartment,” I assured him. “Alright,” he said. “I trust you.”

He began home hospice in January 2022. He turned 69 on March 24. Not long after his birthday, I showed him a video I had seen about Brittany Maynard, a young woman with terminal brain cancer who chose to use Oregon’s medical aid-in-dying law, and to my surprise he watched the entire thing, start to finish. When it was over, he looked at me and said, “Can I get that done?”

I had to tell him that I didn’t think it was available in Nevada, although it was in some other states. It was apparent to me that if Dad had that option, he would have availed himself of it. He was afraid of leaving his home; he didn’t want to be pumped full of liquid morphine like he had seen happen to quite a few of our family members. “Devastating” is an understatement for what they went through. For Dad, passing away in the comfort of his own home would have been a beautiful thing, and I think he knew that with medical aid in dying, that would be more attainable.

Regardless, Dad pushed himself to live as long as he could. On June 8, 2022, he fell in the living room, breaking a bone in his left knee and fracturing his left hip. When the EMTs showed up, he refused to go with them or receive care. He was in his right mind, answering their questions about who the president was with ease. But he just said, “I don’t have to go anywhere.” And they left.

On June 13, I went to bring him his coffee and found him slumped over in his wheelchair. I didn’t think twice — I called 911. Dad was MEDEVACed from our rural area to a Las Vegas hospital, where doctors announced that he had pneumonia and stage 4 COPD. They put Dad on a ventilator and performed a biopsy on his tumor, none of which was what he wanted, but I wasn’t able to get there in time to articulate that to the medical staff.

A few days later, Dad had the ventilator removed. Shortly after that, on June 18 — Father’s Day — I went to see him. I took one look at him and knew it would be the last time. I told him I loved him, and he said he loved me, too. I could tell he was holding back tears. He was still in pain, just dwindling away.

Around 1:00 the following morning, I received a call from Dad’s doctor asking if she had verbal confirmation from his children that his wishes were not to be resuscitated if he were to stop breathing. I said yes, that I didn’t want him to suffer any more than he already had. He died three days later.

It’s absurd to me that someone who is already dying, already suffering, should have to endure more anguish than they already are. The current way the medical system operates in this state is not compassionate, and many people are not informed about what medical aid in dying is or how it works. My father endured months of pain and had no option but to die in a hospital, not at home like he wanted. If medical aid in dying had been available in Nevada, things could have been different.

Mail contributions directly to:

Compassion & Choices Gift Processing Center

PO Box 485

Etna, NH 03750